Wesley Research Institute

Wesley Research Institute (WRI) is a preeminent research institute dedicated to delivering high-impact health and medical research outcomes. Recognised for its substantial contributions to societal health, WRI aspires to be a world leader in health and medical research, achieving excellence and innovation in health outcomes. As WRI embarks on the next phase of its growth strategy, it is committed to establishing itself as one of Australia’s premier research institutes, enhancing its profile as a leader in health and medical research and amplifying the impact of its research through diverse communication channels while fostering robust partnerships with current and potential collaborators.

The Task:

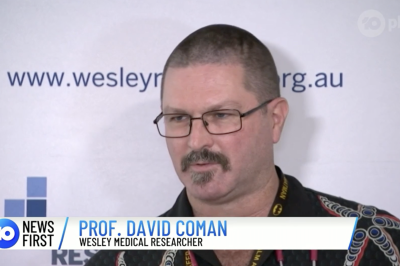

Since 2019, Wings Public Relations has been instrumental in bolstering WRI’s visibility and reputation. We have secured significant media coverage for WRI across various research studies, ensuring that researchers groundbreaking work reaches a broad audience. Recently, our contributions have expanded to encompass the development of a comprehensive communication strategy, including graphic design and strategic advice, particularly supporting WRI’s marketing and communications officer. Our efforts have led to a substantial uptick in visitors to the WRI website and increased content engagement across multiple social media platforms.